I proudly identify as a “dildo slinger” — that’s a much way cooler way of saying “sex toy retail worker.” In addition to writing this blog, I have worked at a local sex toy boutique for nearly 8 years. It’s a unique, misunderstood job, one that often elicits perplexed looks and palpable silence. Rarely is this work given the credit it deserves, so when I picked up Lynn Comella’s Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure, I was relieved to sink into a world where my career was treated with respect and nuance.

Comella has done the work. She’s been in the adult retail industry observing, documenting, and researching since 1998; she conducted over 80 interviews; she even worked at Babeland in New York for 6 months in the early ’00s. In fact, she’s been in the sex toy trenches for so long that at one point she retells a story about attending a launch party for the Je Joue SaSi, a frustrating oral sex simulator that has now been discontinued for years. (They served a drink called the “SaSitini” and I want to know whether it made people want to chuck their glasses across the room?)

Vibrator Nation covers a lot of ground, from the invention of the vibrator1 to the history of feminist sex shops to modern struggles with ethics and profitability. The book is more about brick-and-mortar shops than it is about products, save for one chapter which delves into the politics of stock2 and rather briefly discusses the issue of toxic toys.

Much like The Feminist Porn Book, Vibrator Nation is peppered with academic concepts but never veers so far in that direction that it becomes dry or incomprehensible. Rather, Comella’s more intellectual asides help illuminate the cultural importance of feminist sex shops and how they differ from traditional retail spaces, and the result is a book that is accessible enough for casual readers but scholarly enough to be taught, I hope, in colleges. Would be nice for those whippersnappers to learn the true value of sex shops beyond “places you go with your friends to make fun of stuff”!

The book can feel a bit cursory at times — turns out, people are using vibrators! Buying them, even! — but there are also tons of nitty-gritty details and factoids for sex toy freaks such as myself. For example: rent for Good Vibrations’ tiny first shop in San Francisco cost $125/month! The founders of Babeland considered opening a lesbian club called Speculum! Back when Vixen Creations dildos were poured and packaged in the founder’s house, before sex toys were even a thing, some were returned due to cat hair! (Oh, I know the struggle.)

It opens, obligatorily, with Betty Dodson. A blockquote from her begins “women-run sex shops are the little pockets of sanity around the country” but devolves into a weirdly underhanded statement that “this is where feminism — if there is such a thing — lives if you want to deal with sex.” Oooookay. Why are we debating the existence of feminism in a book about feminism? Why is Betty Dodson continually trotted out as some exemplar of the industry considering she only believes in one sex toy, thinks squirting is a “parlor trick,” and has a pretty questionable understanding of consent?

Granted, there was a history of misinformation and phallocentrism to overcome in Dodson’s time, including Freud’s labeling of the clitoral orgasm as infantile. The reclamation of the clit had to happen. Joani Blank, founder of Good Vibrations, reminisced: “we used to say that the only people who reliably have vaginal orgasms are men.” Ha, nice, but the wholesale rejection of the vaginal orgasm would cause repercussions down the line.

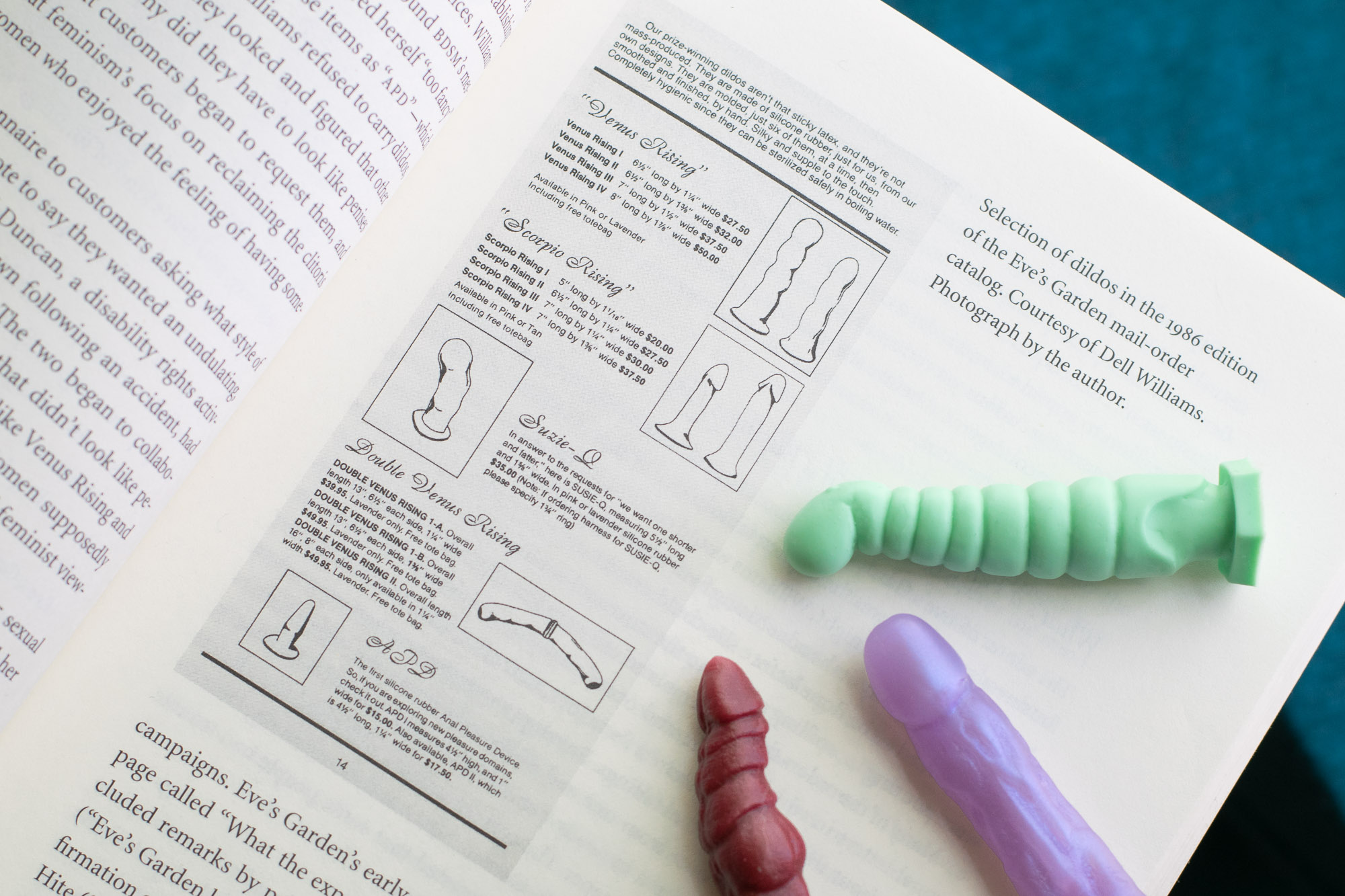

I loved every minute of the story of the first feminist sex toy shop, Eve’s Garden in New York City, founded in 1974 by Dell Williams. At age 52, Williams was a second-wave feminist, a big believer in “energy” and a big disbeliever in dildos. She refused to carry them, and bondage gear was also excluded from her inventory. Williams even came up with an acronym to refer to butt plugs: “APD,” for “anal pleasure devices.” (I audibly chortled.)

Williams founded Eve’s Garden in the hope of empowering women around their sexuality, and she did this by catering to what she perceived as women’s unique sexual sensibilities. These sensibilities, however, closely mirrored her identifications as a primarily heterosexual, white, professional woman. Indeed, Williams’s understanding of female sexuality was rooted in a version of feminism that was largely one-dimensional, focusing on women’s supposed commonality and what she saw as their shared “erotic sisterhood”—views that shaped how she thought about and marketed her business. Williams originally carried a very small selection of products and books that she personally liked and felt comfortable selling, and avoided ones she did not . . . For years, Williams refused to carry dildos, because she personally didn’t like the way they looked and figured that other women didn’t care for them, either. “Why did they have to look like penises was my big thing,” she told me.

That didn’t last forever. Williams eventually agreed to collaborate with Gosnell Duncan, a disability rights activist and the first to make pure silicone dildos, on a line of non-representational dildos to sell at Eve’s Garden. It’s wild to think about how revolutionary this was at the time, considering we now live in a world overflowing with weird dildos — unicorn horns, ice cream, vegetables, and much more — plus an army of simple non-phallic shapes.

Joani Blank opened Good Vibrations in San Francisco in 1977, and descriptions of this time period are downright quaint. The shop was the size of a parking space, they made about $40 each day in sales, and there was even a try-out room where customers could press vibrators against their clothing to gauge strength. Blank had no business plan, no budget, and focused on ethics rather than sales. This freed her from the bounds of capitalism, allowing her to be honest with customers about overhyped products. If clueless dudes came in and knew nothing about their partners’ preferences, Blank told them to go home and talk to them. GOOD.

Not that Good Vibes was perfect, because they also refrained from stocking dildos3 until employee Susie Bright, who once beautifully proclaimed that “penetration is only as heterosexual as kissing,” told Blank that dildos were not solely for chasing the elusive vaginal orgasm, but for enhancing the orgasms people were already having. Imagine that!

Good Vibes easily gets the most page time in Vibrator Nation, and it starts to feel a little limiting after a while. Sporadic quotes and brief stories are included from the owners of Early to Bed, Smitten Kitten, Self Serve, Feelmore, Sugar, and The Tool Shed, but it always loops back to Good Vibes and Babeland, and employee perspectives seem to come almost exclusively from those two companies.

I think delving deeper into the inner workings of smaller (and at this point, less corporate) shops would’ve offered a more comprehensive look. At times Vibrator Nation feels a bit zoomed out, a bit big picture, and as such feels like it’s missing an element of what it’s actually like to work at a feminist sex shop day-to-day. I was amazed to finish the book without ever hearing a peep about creeper phone calls — a facet of the job that, in its darker moments, can make you want to quit on the spot.

I was worried Vibrator Nation might paint these shops as feminist utopias. The overall tone is positive for sure, but the book does contain some much-needed real talk. It was chapter 4, “Repackaging Sex,” that elicited the biggest lightbulb moment from me.

The discourses of distinction that are routinely mobilized by feminist retailers, such as clean versus dirty and sexual safety versus sleaze, not only produce a particular kind of retail environment but also construct an image of an idealized sexual consumer that is perhaps not as encompassing of racial and class diversity as these businesses might hope.

Amy Andre emphasized this point when discussing what she saw as the “hyper-attention paid to cleanliness” at Good Vibrations: “We kept emphasizing the clean and brightly lit store, and I think [these things] have very definite class and race implications that were never explicitly stated; but I think it was a way of saying, ‘You won’t encounter black men or poor men here. You won’t encounter people here who are physically having a sexual experience in this location . . . Nobody is going to think you are the bad girl in this place or that you are a sex worker because you are entering a toy store.’ I think there was a lot that wasn’t being said when we were communicating to customers.”

This inspired me to think critically about language, to be more careful in how I conceptualize where I work to others. It made me realize how descriptors such as “classy,” “upscale,” “tasteful,” and “clean” create a false hierarchy, one that positions feminist shops as superior to other sex shops — and implies they’re the most in tune with “women’s” desires, which is problematic on many levels. Not all customers want to shop in such a sanitized, desexualized environment,4 and in fact prefer the anonymity and taboo of more traditional adult shops.

Whether or not shop owners consciously acknowledge it, “female friendly” is often code for a target demographic of white, affluent, straight cis women. And it’s no wonder, considering many feminist sex shops were founded by white women with economic capital.

Yet sex shop employees often struggle to get by — expected to accept basic retail wages when the work is far more nuanced and emotionally demanding than selling shoes or sandwiches. The owners of Babeland and Grand Opening were apparently surprised when workers unionized — but why? Did they think their feminist values would magically trickle down to employees? It requires a concerted effort to support your employees, and the sad reality is that some sex shops just don’t. Store credit can’t pay rent, and as Babeland employee Lena Solow put it, “it’s not enough to just respect people’s pronouns. A trans person not being able to take sick time is a feminist issue.”

At least the veneer of capitalism can be a comfort for the consumer. Customers understand how to navigate a retail environment, where browsing and asking questions is encouraged and monetary transactions are optional. Sex shops are more accessible than health clinics or therapy offices, which often require a slew of bureaucratic bullshit. Comparatively, customers need not have a “problem” to visit a sex shop, and it costs nothing to walk through the door. Sex shops aren’t always selling products, necessarily — often they are selling emotions, reassurance, and conversations with people who will listen without judgment.

For me, this was the most affirming part of Vibrator Nation: the way it presents sex toy retail with such love and care. Page after page, Comella articulates how vital and transformative this work can be, even if it sometimes feels frustrating and redundant. Vibrator Nation is an essential history of an overlooked industry, its place in the world of sex education and commerce, and a reminder of the work that still needs to be done.

In the early days of Eve’s Garden, Dell Williams received all kinds of letters from customers. Some expressed offense at her shop: “I am not quite sure what feminists are doing in the vibrator business (it seems rather anti-social and anti-people).” Others penned amazing precursors to modern sex toy reviews: “as soon as I flipped the switch on the Prelude 3, I knew it for a timid, half-hearted wimp of a thing.” But what struck me most was that so many letters ended with “thanks for listening” or “thanks for being there.” 40 years later, and that’s something we still hear from customers. It’s the reason we soldier on.

Get Vibrator Nation at Smitten Kitten or Powell’s.

- One 1917 ad promised their vibrator would cause “such a wholesome, sparkling degree of vigor that life will present a new aspect to the man or woman who has moped along in a semi-invalid condition for a long period”

- “The products they sell are the material expression of their feminist values and sex-positive principles . . . a willingness to forgo profits that might otherwise result if retailers offered people a quick fix to a perceived sexual problem or played on their sexual anxieties.”

- Blank’s viewpoint “wasn’t so much antidildo as it was proclit”

- Former manager Cathy Winks described Good Vibrations as “almost oppressively countererotic”