In high school, words were my power. Nobody paid attention to me otherwise.

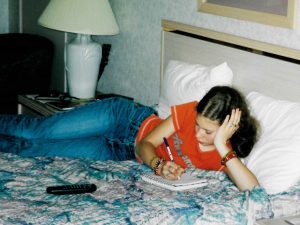

I was a queer kid coming of age in the early ’00s in the stifling suburbs. Many kids at my school were hicks or Christians, or some toxic mash-up of both. Bush was president for what felt like an eternity. I ate more strawberry cheesecake ice cream than one should eat in a lifetime and stayed up late to catch the gay makeouts on Undressed. I wrote feverishly and journaled constantly, about my broken heart and fights with my parents and cute girls at school, all of whom were straight and unattainable.

Trying to fit in was out of the question. I wore orange corduroy pants, a green checkered shirt, Converse with poems scrawled on the soles. Bracelets consumed my wrists. My mom sewed a rainbow stripe onto my backpack. On the bus with my closest friend, we listened to the people behind us catch up on gossip. “Wouldn’t it be weird if we were like them?” my friend whispered to me.

I replied, “yes, very.”

The only people I wanted to be around were the artists. At school, my sanctuary was a room lined with iMacs and a slouching old couch: the journalism newsroom. I often spent lunches alone there, eating quietly alongside my teacher, surfing the internet, or bantering with fellow newspaper staff. Every two weeks, we stayed after school to finish the newspaper, scarfing $5 pizzas from Little Caesar’s and transferring stories from floppy disk to page. Sometimes, we’d wander the empty halls looking for inspiration.

I wrote dramatic, impassioned columns for the opinion section on such riveting subjects as mix CDs, dying drive-in movie theaters, my recently-adopted three-legged cats, keeping a journal, and the absurdity of school dances. I designed page layouts and shot photos. I wrote news stories, features, and reviews of movies (Almost Famous rightfully given a glowing endorsement) and music (rating a Simon and Garfunkel concert 5 stars, obviously: “Garfunkel’s voice sounded as smooth as Jell-o sliding off a spoon”).

Then, my junior year, I wrote a column entitled Gay Marriage Will Not Bring About the Apocalypse. Which, as you can extrapolate from the headline, felt like the way it needed to be framed to have any hope of reaching my conservative classmates. Start by just saying the world won’t end! The column was in response to a prior guest column about the perils of gay marriage. It was 2004 — the height of gay marriage panic.

I was biting, sarcastic, armed with facts and indignation. My column ended with the mic drop line, “no one has to accept anything — only the fact that gay marriage is inevitable.”

That fall, measure 36 proposed a change to the Oregon constitution, to define marriage as between one man and one woman. The drive to school was a parade of lawn signs. Kids came to school with YES ON 36 bumper stickers on their binders. I saw a shirt reading I WON’T BE REDEFINED — YES ON 36.

I collected these little signs, stowing them away. I noticed how the winter formal sign-up sheet had columns for “guy” and “girl,” how classmates scrunched their noses when they saw the suggestive girls plastered on my journals, how the school required permission slips for students to audition for The Laramie Project.

At home, anonymous screennames bullied me on AIM, naming female teachers, asking me who was hottest. My brother called me a dyke. Once, a girl physically recoiled from me.

They had their bigotry, but I had something stronger: ink, imprinted on paper, real and indisputable.

Senior year, I became Opinion Editor.

They had their bigotry, but I had something stronger: ink, imprinted on paper, real and indisputable.

I don’t know when I decided I was going to write a coming out column. I just know that at some point, it became inevitable. For 4 years I’d poured myself into journalism, lugging around a tape recorder and hunting down uninspiring interview subjects, hating it, working my way up until I no longer had to talk to a single soul in order to write my stories. Just how I wanted it. I was my source.

It would be the truest thing I could possibly write. My final fuck you.

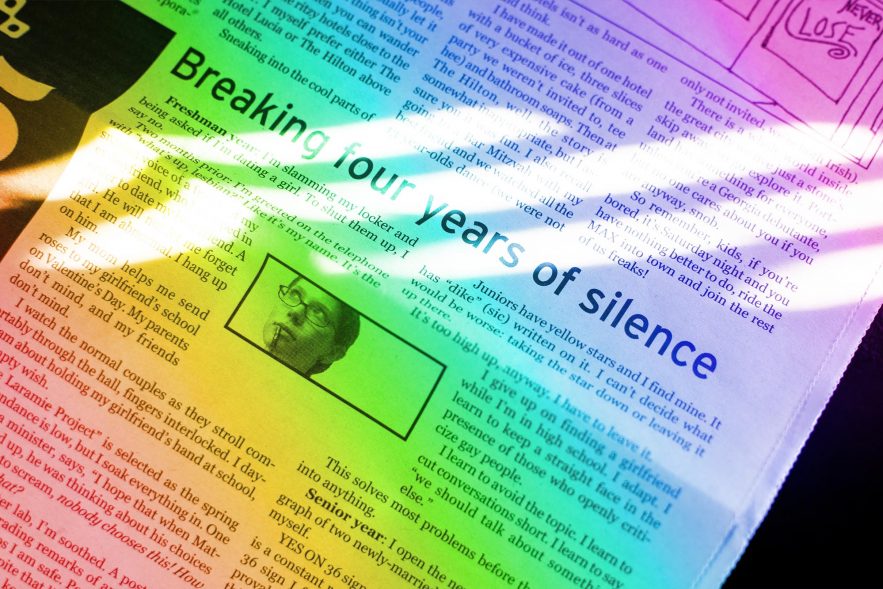

My column appeared in Volume 37 and Issue 16 of my high school paper, published Friday, May 6th, 2005, right before I graduated, on page 3. The front page headline was about a crackdown on students without hall passes. My column appeared on page three, next to a list of the top 5 weirdest examples of actual graffiti in the school bathrooms.

It was my magnum opus, and they printed all 700 words of it.

This column later won Best in Category at the statewide Publications Olympics — my amazing

journalism teacher submitted it for me. Here it is in full, unedited from its printed form.

Breaking Four Years of Silence

May 6th, 2005

Freshman year

I’m slamming my locker and being asked if I’m dating a girl. To shut them up, I say no.

Two months prior: I’m greeted on the telephone with “what’s up, lesbian?” Like it’s my name. It’s the snarled voice of a friend of my ex-boyfriend, who I dumped in order to date my best friend. A girl. He will not let me forget that I am abnormal. I hang up on him.

My mom helps me send roses to my girlfriend’s school on Valentine’s Day. My parents don’t mind, and my friends don’t mind.

I watch the normal couples as they stroll comfortably through the hall, fingers interlocked. I daydream about holding my girlfriend’s hand at school, an empty wish.

The Laramie Project is selected as the spring play. Attendance is low, but I soak everything in. One character, a minister, says, “I hope that when Matthew was tied up, he was thinking about his choices in life.” I want to scream, nobody chooses this! How can you think that?

In the computer lab, I’m soothed. A poster says “no degrading remarks of any kind will be tolerated.” Perhaps I am safe. Perhaps my classmates will like me despite that little detail. Perhaps I can keep it from them, keep them ignorant.

Four years seems like a lot of pretending.

When they find out, my girlfriend’s parents forbid me from seeing her. Despite promises of persevering, we break up. They get what they wanted.

In English, we take a strange survey. What would you do if your friend told you she was gay? “I’d stop being friends with her,” says a girl I was attracted to before she spoke. “It would just be too weird.”

This is the first lesson in restraint.

In English, we take a strange survey. What would you do if your friend told you she was gay? “I’d stop being friends with her,” says a girl I was attracted to before she spoke. “It would just be too weird.”

Sophomore year

I sometimes like boys. This is a good sign. I can relate to people who swoon over Johnny Depp. Soon it becomes easy to ignore my attraction to girls. I banish the thoughts before they have a chance to materialize. I can look at any beautiful girl and for only half a second consider dating her. Then it’s easy to tell myself no.

Various sources tell me it’s a phase. I’m just confused; it’s impossible to be bisexual; I am flat-out “wrong” for liking girls. They say I’m greedy for liking both sexes, like it’s a crime. Like I’m a murderer.

Junior year

Outside the main office, paper stars are up because all of us are stars at this school. Juniors have yellow stars, and I find mine. It has “dike” [sic] written on it. I can’t decide what would be worse: taking the star down or leaving it up there.

It’s too high up, anyway. I have to leave it.

I give up on finding a girlfriend while I’m in high school. I adapt. I learn to keep an unresponsive face in the presence of those who openly criticize gay people. I learn to avoid the topic. I learn to cut conversations short. I learn to say “we should talk about something else.”

This solves most problems before they blossom into anything.

Senior year

I open the newspaper to a photograph of two newly-married women, and I smile to myself.

YES ON 36 signs fill up yards. My drive to school is a constant reminder. Every time I see a YES ON 36 sign I feel the stab of another person’s disapproval, another person demeaning me into something less than human. I vote; I press my pen hard into the “no” bubble.

I watch the Defense of Marriage Coalition celebrate their “victory” on TV. They’re yelling and hugging and smiling as though someone has won the lottery. I think, it must feel really good to ruin people’s lives.

I find a boyfriend. Our tastes in girls differ, but I am happy. I go to Melissa Etheridge concerts, look at Pride Parade photos, and buy rainbow shoelaces. I write things and attempt to plead my case.

I guess I am being brave. I guess I have guts.

In class we’re asked, “have you ever been in love?” And I can feel the word at the back of my throat, the vague word yes.