Wedged between my consumption of Fast Food Nation and We Need to Talk About Kevin, I inhaled The Feminist Porn Book. I wrote in the margins and bent the pages and even took it in the bath. When I was a stupid teen, I inherited a waterlogged book from a friend, and ever since I’ve secretly wished I’d “accidentally” drop a book in the bath, thereby giving it “character.”

But The Feminist Porn Book has a lot of character without my vain attempts. Its cover is splashed with the most exquisite neon orange and yellow, the huge text like a sledgehammer, and the decisive name declaring that yes, this is the one and only, the definitive feminist porn book, because IT IS.

Flipping open the book, I’m immediately transported back to college. The pages are thin, the line spacing tight, the font reminiscent of many other overpriced essay collections I had to read for school. I like it and also dislike it!

As explained in the introductory essay, this book builds upon previous theory-heavy porn scholarship, like Linda Williams’s Porn Studies and Pamela Church Gibson’s More Dirty Looks, with one major addition — the voices of actual feminists creating and performing in porn.

But this is not, as you might hope and/or fear, a back-patting, confetti-throwing celebration of feminist porn. In fact, at times it is surprisingly critical of the genre. Sometimes this criticism is warranted (as in Tobi Hill-Meyer’s important essay on the exclusion of trans women in porn); other times it is… puzzling, to say the least.

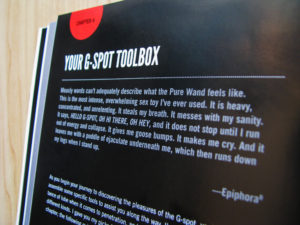

For example. Betty Dodson’s essay has its strong moments (“That night I decided to forget about defining erotic art as being superior to pornographic images”), but she thrashes all of her good points to pieces when she trots out her old school, sex-negative disdain for female ejaculation (seriously, Betty, build a bridge and get over it).

Similarly, Candida Royalle’s essay is benign enough, until out of the blue she starts slamming female pornographers:

When I watch porn directed by a woman I’m hoping to see something different, innovative, something that speaks to me as a woman. All too often I find myself disappointed by what turns out to be the same lineup of sex scenes containing the usual sex acts, sometimes more extreme, following the same old formula, and ending in the almighty money shot. Rather than creating a new vision, it seems many of today’s young female directors, often working under the tutelage of the big porn distributors, seek only to prove that they can be even nastier than their male predecessors.1 And it’s not so much the type of sex that offends me, it’s the crude in-your-face depiction that seems more interested in shock value than anything female viewers might enjoy. Do they really think that most women are going to be turned on by seeing a woman screwed in every orifice by a bunch of seedy guys who finally relieve themselves on her face? And if they’re not concerned with what women want, should it then be considered feminist?

Ms. Out-of-Touch Royalle goes on to declare that feminist porn has been perverted into a male-run domain. Um, no. Way to be a wet blanket, Candida.

Speaking of wet blankets, there is surprisingly little discussion in this book of anti-porn activists such as Gail Dines, Andrea Dworkin, Catharine MacKinnon, Robert Jensen, and Shelley Lubben. I was hoping for some badass take-downs, but found only one — Clarissa Smith and Feona Attwood’s essay on anti-porn rhetoric. The whole essay is a burn, basically, which is to say I loved it.

The writing in The Feminist Porn Book is at times breezy, at times very dense. I had to skim a few essays, like those by Ariane Cruz, Kevin Heffernan, and Bobby Noble, because they felt too much like trudging through mud. You know the kind — the kind of essay which tells you in advance what it is about to prove/say/do. Yet it is these very essays that will make this book prescribable in an academic setting, so I will allow them.

But one essay that takes things way too far is Celine Parreà±as Shimizu’s “Bound by Expectation: The Racialized Sexuality of Porn Star Keni Styles,” which elicited the most margin notes from me, including “uhhh,” “wut, “omg,” and “u mad?” I’ll admit I didn’t do the deepest reading of this essay, because it is very scholarly and its examples pretty preposterous. But it discusses Keni Styles’ educational video Superman Stamina (which, by the way, sounds like macho crap), and analyzes his role in Tristan Taormino’s film Rough Sex 3.

I like reading too much into things as much as the next guy (I once wrote a 10-page paper arguing that the goblins in “Goblin Market” fit the anger-retaliatory rapist subtype), but I was perplexed by the conclusion that Keni’s race is somehow a factor in why he doesn’t get a ton of screen time in Rough Sex 3. I re-watched the scene and yeah, as I mentioned, Keni’s role is brief, but I doubt it has to do with the fact that he’s Asian. I always assumed he just came too fast.

P.S. That scene is still so freaking hot.

I’d rather leave the philosophizing to the porn performers themselves. Essays like those by Jiz Lee, Danny Wylde, Sinnamon Love, Nina Hartley, April Flores, Buck Angel, Dylan Ryan, and Loree Erickson paint a picture of diverse, headstrong performers unwilling to accept the status quo.

And I know I’ve talked some shit about Lorelei Lee (what can I say, her moans sound like neighs to me), but her essay “Cum Guzzling Anal Nurse Whore: A Feminist Porn Star Manifesta” is spot-on, intertwining her story of entering and performing in porn with deft retaliation against anti-porn discourse. “They fail to realize,” she writes, “that ideas of femininity might be reflected in some porn, but are not caused by it.” PREACH.

Other enlightening moments take place when authors examine their privileges and pick apart their assumptions, as when Ms. Naughty forces herself to understand why “porn for women” can be a limiting and alienating phrase, Dylan Ryan concedes that she is able to “raise [her] conceptual fist to the mainstream because [she] is close enough to the mainstream to even be let inside in the first place,” Keiko Lane regrets shaming a client for having kinky fantasies, and Buck Angel admits that he once felt his vagina made him “less of a man.”

Lorelei Lee intertwines her story of entering and performing in porn with deft retaliation against anti-porn discourse. “They fail to realize,” she writes, “that ideas of femininity might be reflected in some porn, but are not caused by it.”

Jane Ward’s “Queer Feminist Pigs: A Spectator’s Manifesta,” which immediately reeled me in when it asked “can we watch sexist porn and still have feminist orgasms?”, made me squeal in delight. I was hoping for a bit more on how to achieve queer viewings of mainstream porn, but still very much enjoyed that one.

I also loved Keiko Lane’s “Imag(in)ing the Possibilities: The Psychotherapeutic Potential of Queer Pornography,” which sounded like it was going to make me yawn. Instead it punched me in the gut, as when she wrote about gay men who lived through the AIDS epidemic:

They know about safer sex and how to make safe sex hot, and many of them report no conflict in their actual, embodied sexual lives about HIV status or precautions. But what they long for is a time or place immune to fear. We talk about the ways in which they use pornography that depicts unprotected sex as an act of rememberance of a kind of sexuality unhindered by fear of contamination. Porn that features unprotected sex is the iconography of their loss.

OK, sobbing.

And Tristan Taormino’s essay is, of course, great, even if much of the information in it has been culled from her “My Life as a Feminist Pornographer” talk. She is the most explicit about the nitty-gritty details that comprise ethical porn-making: consent, communication, fair pay, safety, diversity without commodification, freedom for performers to participate in their own representation, and all the snacks, sex toys, and safer sex supplies on set that a performer could ever need.

In a perfect world, I would’ve loved to read additional essays by Belladonna, Sasha Grey, Violet Blue, Joanna Angel, Adrianna Nicole, and Mickey Mod. Perhaps they were contacted and declined; I don’t know. It is also odd that Shine Louise Houston didn’t write something, despite being practically the most name-dropped person in the book.

But I’ll survive. As it is, The Feminist Porn Book is an amazing contribution to the world. I have a feeling it may become a classic. It is interesting, challenging, and eye-opening. Academic at times, but not suffocatingly so. It has its weird moments, but those just serve as a fun opportunity to flail in the margins, and to further appreciate the essays from more progressive voices.

Also, it goes really well with a good cat friend and a mug of cocoa.

Get The Feminist Porn Book at Powell’s or Good Vibes.